Actuators: The Essential Cornerstone of Modern Motion Control

In a world increasingly defined by automation and precision engineering, one component stands quietly at the heart of nearly every mechanical system: the actuator. From the adjustable hospital bed that provides comfort to recovering patients, to the massive hydraulic systems controlling aircraft landing gear, to the motorized standing desk in your office—actuators are the unsung heroes converting energy into controlled, purposeful motion.

An actuator is fundamentally a device that converts various forms of energy—electrical, hydraulic, pneumatic, or even piezoelectric—into mechanical force and motion. Think of actuators as the muscles of the machine world. Just as your muscles convert biochemical energy into the physical movement of your arms and legs, actuators enable machines to push, pull, rotate, lift, and position components with remarkable precision. Despite rarely making headlines like artificial intelligence or robotics, actuators are the foundational technology that makes these advanced systems possible in the first place.

This comprehensive guide explores everything you need to know about actuators: how they work, the different types available, how to select the right actuator for your application, installation best practices, and the diverse industries that depend on them daily. Whether you're an engineer specifying components for an industrial system, a DIY enthusiast planning a home automation project, or simply curious about the technology that powers modern machinery, this article will provide the technical depth and practical insights you need.

Fundamentals of Actuator Technology

At its core, an actuator is a transducer—a device that converts one form of energy into another. Specifically, actuators convert input energy from electrical current, hydraulic fluid pressure, compressed air, or other sources into controlled mechanical motion. This seemingly simple function is what enables the vast majority of automated systems and machinery we rely on every day.

How Actuators Work

The operational principle of an actuator depends on its type and energy source. Linear actuators that run on electricity use a DC motor connected to a gearbox and lead screw assembly. When electrical current flows through the motor, it creates rotational motion. The gearbox reduces the speed while increasing torque, and the lead screw converts this rotary motion into linear push-pull movement. Built-in limit switches at each end of the stroke prevent over-extension and protect the mechanism.

Hydraulic actuators operate on Pascal's principle—pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted equally in all directions. By forcing incompressible hydraulic fluid into a cylinder, immense force can be generated to move a piston rod. These systems excel in applications requiring substantial force, such as construction equipment, aircraft controls, and industrial presses.

Pneumatic actuators function similarly to hydraulic systems but use compressed air instead of fluid. While they typically generate less force than hydraulic systems, pneumatic actuators offer cleaner operation, simpler maintenance, and faster actuation speeds. They're commonly found in automation systems, manufacturing equipment, and tools requiring rapid cycling.

The Critical Role of Actuators in Modern Systems

While actuators may not capture public attention like artificial intelligence or machine learning, they occupy an indispensable position in modern technology. Consider that there are billions of actuators operating globally at any given moment—in vehicles, industrial machinery, medical devices, consumer products, and building systems. Without actuators, concepts like automation, robotics, and smart systems would remain theoretical impossibilities.

In automotive systems alone, a modern vehicle contains dozens of actuators controlling everything from throttle position and transmission shifting to power windows, seat adjustments, and climate control dampers. In industrial settings, industrial actuators enable precise control of robotic arms, conveyor systems, and automated assembly lines. The medical field depends on actuators for adjustable beds, surgical robots, patient lifts, and diagnostic equipment positioning.

Comprehensive Guide to Actuator Types

Actuators come in numerous varieties, each engineered for specific applications, performance requirements, and environmental conditions. Understanding the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each type is essential for selecting the right actuator for your project.

Electric Linear Actuators

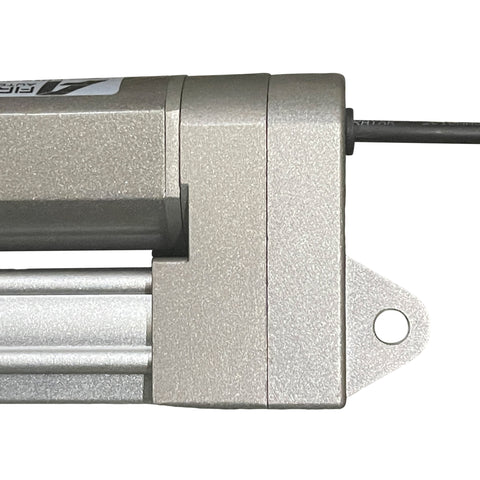

Electric linear actuators are the workhorses of motion control, converting electrical energy into precise linear push-pull motion. These devices consist of a DC motor, gearbox, lead screw or ball screw mechanism, and housing—all integrated into a compact, reliable package. The motor drives the gearbox, which reduces speed and increases torque. This rotational motion is then converted to linear motion through the screw mechanism.

Available in a wide range of configurations, electric linear actuators can provide forces from just a few pounds up to several thousand pounds, with stroke lengths ranging from under an inch to several feet. Common voltage options include 12VDC and 24VDC for mobile and automotive applications, as well as 110VAC and 220VAC for stationary industrial installations. Speed typically ranges from 0.5 to 2 inches per second, though this varies inversely with force—higher force models generally operate more slowly.

Key advantages of electric linear actuators include precise position control, quiet operation, clean operation with no fluid leaks, relatively simple installation, and compatibility with electronic control systems. They're ideal for applications in home automation, medical equipment, TV lifts, adjustable furniture, robotics, and light to medium industrial automation. For extremely compact installations, micro linear actuators offer linear motion in remarkably small form factors.

Track and Slide Actuators

Also known as slider actuators or track actuators, these specialized linear actuators incorporate a rigid track or rail system that guides the moving carriage. This design provides superior lateral stability compared to traditional rod-style actuators, making them ideal for applications where side loads or moments are present. The guided carriage can support higher perpendicular loads without binding or premature wear.

Track actuators find extensive use in camera slider systems for film and photography, automated conveyor systems, CNC machinery, and precision positioning stages. They excel in applications requiring smooth, stable motion along a defined path, particularly where the load isn't perfectly aligned with the direction of travel. FIRGELLI's track actuator designs integrate the motor, drive mechanism, and guide system into a unified assembly, simplifying installation and improving reliability.

Rotary Actuators and DC Gear Motors

Rotary actuators, often called DC gear motors, produce rotational motion rather than linear travel. These devices consist of an electric motor coupled to a gearbox that reduces speed while increasing torque. An electric motor running at high RPM with low torque isn't practical for most applications—the gearbox transforms this into usable rotational power at appropriate speeds and torque levels.

In fact, DC gear motors are fundamental components within linear actuators themselves. A linear actuator is essentially a rotary actuator with the addition of a lead screw mechanism and limit switches to convert and control the rotational motion into linear travel. Understanding this relationship helps clarify how force, speed, and power characteristics translate between rotary and linear motion systems.

Rotary actuators power an enormous range of applications: valve actuation in industrial processes, robotic joint control, automotive windshield wipers, automated gate operators, solar panel tracking systems, and industrial mixing equipment. They're available in torque ratings from fraction ounces-inch for precision instruments up to thousands of pound-feet for heavy industrial machinery.

Hydraulic Actuators

Hydraulic actuators leverage incompressible fluid—typically oil—to generate substantial force and motion. These systems consist of a hydraulic pump, reservoir, control valves, hoses, and the actuator cylinder itself. When the pump forces fluid into the cylinder, the pressure acts on the piston surface area, creating force according to the basic relationship: Force = Pressure × Area.

The primary advantage of hydraulic systems is their exceptional power-to-weight ratio. A relatively compact hydraulic cylinder can generate tens of thousands of pounds of force, making them indispensable for heavy construction equipment, aircraft flight control surfaces, industrial presses, and large-scale manufacturing machinery. Hydraulic actuators can also maintain force indefinitely without consuming energy, as the incompressible fluid holds position mechanically.

However, hydraulic systems come with complexity, maintenance requirements, potential for fluid leaks, and higher initial costs. They require pumps, reservoirs, filtration systems, and careful fluid management. Environmental concerns about hydraulic fluid leaks have driven many applications toward electric alternatives in recent years, particularly where the extreme force capabilities of hydraulics aren't essential.

Pneumatic Actuators

Pneumatic actuators use compressed air or gas to create motion, operating on principles similar to hydraulic systems but with a compressible working fluid. Air is compressed by a compressor, stored in a receiver tank, and then directed through control valves to actuator cylinders. The expanding air drives a piston to create linear motion, or rotates a vane for rotary motion.

Pneumatic systems offer several distinct advantages: clean operation with no fluid contamination, inherent explosion-proof safety in hazardous environments, simple and robust construction, and fast actuation speeds. They're extensively used in factory automation, packaging equipment, automotive assembly lines, and any application requiring rapid cycling. The compressibility of air also provides natural cushioning at the end of strokes.

The limitations of pneumatic actuators include lower force output compared to hydraulic systems of similar size, less precise position control due to air compressibility, and the need for compressed air infrastructure. Energy efficiency can also be a concern, as compressed air systems typically lose significant energy to heat and leaks.

Piezoelectric Actuators

Piezoelectric actuators represent a fundamentally different approach to motion generation. These devices use piezoelectric materials—typically specialized ceramics—that change dimension when subjected to an electric field. By precisely controlling the applied voltage, extremely fine positioning adjustments can be achieved with resolutions in the nanometer range.

The defining characteristics of piezoelectric actuators are exceptional precision, high stiffness, very high force for their size, and extremely fast response times measured in microseconds. They're essential in applications like atomic force microscopes, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, precision optical systems, and high-end audio equipment. Research laboratories use them for nano-positioning stages that manipulate individual atoms and molecules.

The significant limitation of piezoelectric actuators is stroke length—typical displacement ranges from a few microns to perhaps 10mm at most for stacked designs. They're not suitable for applications requiring substantial travel, but nothing matches their precision within their limited range. They also require high-voltage drive electronics and exhibit some hysteresis and creep behavior that must be compensated for in precision applications.

Actuator Applications Across Industries

The versatility of actuators enables their integration into virtually every sector of modern industry and commerce. Understanding typical applications helps clarify which actuator types best serve specific needs and provides insight into design considerations for custom implementations.

Industrial and Manufacturing Applications

Manufacturing and industrial automation represent one of the largest application domains for actuators. Robotic assembly lines depend on precise actuator control for pick-and-place operations, welding, painting, and material handling. Conveyor systems use actuators for diverters, gates, and positioning mechanisms. CNC machinery employs actuators for tool positioning and workpiece clamping. In each case, reliability, repeatability, and precise control are paramount.

Industrial actuators must withstand demanding environments including temperature extremes, vibration, contamination from dust or fluids, and continuous duty cycles. They often feature enhanced sealing, robust construction, and industrial-grade components rated for millions of cycles. Integration with programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and industrial networking protocols enables coordinated control of multiple actuators within complex automated systems.

Medical and Healthcare Applications

Healthcare applications demand actuators that combine precise control, quiet operation, and absolute reliability. Hospital beds use multiple actuators to adjust head, foot, and overall height positions, enabling optimal patient positioning and caregiver ergonomics. Surgical robots depend on extremely precise actuator control for minimally invasive procedures where movements must be measured in millimeters. Patient lifts and mobility aids use actuators to safely transfer patients with reduced physical effort from caregivers.

Medical diagnostic equipment such as CT scanners, X-ray tables, and examination chairs all incorporate actuators for positioning patients and equipment. Dental chairs, optometry equipment, and physical therapy devices similarly rely on smooth, controlled motion. The medical sector's stringent requirements for safety, cleanliness, and reliability make electric actuators particularly attractive—they operate cleanly without hydraulic fluid contamination risks and provide the precise control essential for medical applications.

Automotive and Transportation

Modern vehicles incorporate dozens of actuators for comfort, convenience, safety, and performance systems. Power windows, door locks, trunk releases, seat adjustments, steering column tilt, and pedal position all use actuators. Climate control systems employ multiple actuators for damper control, temperature mixing, and air distribution. Advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) use actuators for adaptive cruise control, lane keeping, and automatic emergency braking.

In commercial vehicles and specialty equipment, actuators control dump bed raising, fifth-wheel adjustment, landing gear deployment, and hydraulic stabilizers. Recreational vehicles use actuators extensively for slide-out rooms, leveling jacks, awning deployment, and TV lifts. Marine vessels employ actuators for trim tabs, hatch operation, and stabilizer control. The 12VDC and 24VDC electrical systems common in vehicles make electric actuators particularly well-suited for these mobile applications.

Furniture and Ergonomic Applications

The evolution toward adjustable, ergonomic furniture has created substantial demand for actuators in residential and commercial furniture. Height-adjustable standing desks use synchronized actuators in each leg column to smoothly raise and lower work surfaces, addressing the health concerns associated with prolonged sitting. Recliners and adjustable chairs use actuators for back angle, footrest position, and lumbar support adjustment.

In professional environments, control room consoles, laboratory benches, and workstations increasingly feature actuator-driven height adjustment to accommodate different operators and tasks. Kitchen furniture is beginning to incorporate height-adjustable countertops and work surfaces for accessibility and ergonomics. The furniture sector typically requires quiet operation, smooth motion, and aesthetically clean integration of actuation components.

Home Automation and Smart Buildings

Smart home technology increasingly relies on actuators to automate and remotely control various household systems. Motorized window treatments use micro actuators or rotary motors for convenient, scheduled, or sensor-triggered operation. Automated skylight openers provide ventilation control based on temperature or air quality. Security applications include automated door locks, window locks, and safe mechanisms.

Home theater systems often feature motorized projection screens and TV lifts that reveal or conceal displays as needed. Kitchen applications are emerging for lift-up appliance storage, automated spice racks, and adjustable shelving. In commercial buildings, actuators control HVAC dampers, automated doors, window washing rigs, and building facade elements. Integration with building automation systems and smart home platforms enables sophisticated control schemes coordinating multiple actuators.

Aerospace and Defense

Aerospace applications represent some of the most demanding actuator requirements, combining extreme reliability needs with challenging environmental conditions and weight constraints. Aircraft flight control surfaces—ailerons, elevators, rudders, flaps, and slats—all depend on precise actuator control. Landing gear deployment and retraction, cargo door operation, and emergency systems like ram air turbine deployment use specialized actuators designed to aerospace standards.

While hydraulic actuators have traditionally dominated aerospace applications due to their exceptional power-to-weight ratio, the industry is gradually transitioning toward electric systems for reduced maintenance, improved efficiency, and elimination of hydraulic fluid fire hazards. This "more electric aircraft" trend is driving development of high-performance electric actuators capable of meeting aerospace duty cycles and environmental extremes.

Renewable Energy Systems

Renewable energy generation depends heavily on actuators for optimizing energy capture. Solar tracking systems use rotary actuators or linear actuators to adjust panel angles throughout the day, following the sun's path for maximum exposure. Dual-axis tracking systems require coordination of multiple actuators for azimuth and elevation control. Studies show properly controlled tracking systems can increase energy capture by 25-45% compared to fixed installations.

Wind turbines incorporate numerous actuators for pitch control of rotor blades, yaw drive for nacelle orientation, and brake systems. Proper blade pitch control is essential for optimizing energy capture in varying wind conditions and protecting the turbine in high winds. Hydroelectric installations use actuators for gate control and flow regulation. The outdoor, sometimes remote, locations of renewable energy systems require actuators with robust weatherproofing and reliable operation across wide temperature ranges.

How to Select the Right Actuator for Your Application

Choosing the appropriate actuator requires systematic evaluation of your application requirements against the capabilities and specifications of available actuator types. Following a structured selection process ensures you specify an actuator that will perform reliably while avoiding over-specification that increases costs unnecessarily.

Step 1: Determine Required Motion Type

The first fundamental decision is whether your application requires linear or rotary motion. If you need to push, pull, extend, retract, lift, or lower something in a straight line, you need a linear actuator. If you need to rotate, spin, turn, or pivot something, you need a rotary actuator.

For linear applications, determine whether a traditional rod-style actuator will work or if your application would benefit from a track actuator that provides better lateral stability. Consider the stroke length required—the full distance the actuator must travel. For very compact installations, bullet actuators offer linear motion in miniature packages.

Step 2: Calculate Force Requirements

Determining the required force is critical for actuator selection. Begin by identifying the weight or resistance the actuator must overcome. For lifting applications, this is straightforward—calculate the weight of the object. However, remember that force requirements often vary throughout the stroke depending on geometry and mechanical advantage.

For applications involving hinged mechanisms like trunk lids, hatches, or adjustable furniture, the force required typically peaks at specific angles and may be much less at other positions. Consider the mounting geometry carefully—actuators mounted at angles or creating torque about a pivot point will require more force than simple direct lifting. Online calculators and basic trigonometry can help determine forces for various mounting configurations.

Critical safety consideration: Never specify an actuator at its maximum rated force for continuous operation. Build in a safety margin of at least 50%. If calculations indicate you need 100 lbs of force, specify an actuator rated for 150-200 lbs. This safety factor accounts for friction, binding, load variations, and ensures the actuator isn't constantly operating at maximum capacity, which would reduce service life and reliability.

Step 3: Assess Precision and Control Requirements

Determine whether your application requires knowledge of actuator position during travel or if simple extend/retract operation is sufficient. Standard actuators move until they reach built-in limit switches at each end of stroke. They don't inherently know where they are mid-stroke unless you provide external sensing or a signal to stop them.

If you need to position something at specific intermediate locations, synchronize multiple actuators precisely, or implement closed-loop control, you need feedback actuators. These incorporate Hall effect sensors, optical encoders, or potentiometers that provide continuous position feedback. This allows a controller to monitor and command precise positions throughout the stroke.

Consider whether you need to coordinate multiple actuators operating simultaneously. Applications like four-corner desk lifting, synchronized hatch opening, or coordinated robotic motion require feedback actuators connected to a controller that can read position signals from all actuators and adjust their speeds to maintain synchronization regardless of load variations. FIRGELLI's control systems can manage multiple synchronized feedback actuators for these demanding applications.

Step 4: Consider Speed Requirements

Actuator speed is typically measured in inches per second for linear models or RPM for rotary actuators. Consider how quickly the motion must occur—some applications like safety systems require rapid actuation, while others like adjustable furniture prioritize smooth, quiet motion over speed.

Understand that speed and force are inversely related in actuator design. Higher force models generally operate more slowly because they use higher gear ratios to increase torque. If your application requires both high speed and high force, you may need to consider larger actuators, alternative technologies, or redesigning the mechanical advantage of your system.

Step 5: Evaluate Power Requirements

Identify what electrical power is available in your application. Mobile applications like vehicles, boats, and RVs typically have 12VDC or 24VDC power available. Residential and light commercial installations generally have 110VAC available, while industrial settings may have 220VAC or 480VAC three-phase power. Specify actuators compatible with your available power to avoid the complexity and cost of adding power supplies or converters.

Consider the current draw of the actuator, especially for battery-powered or mobile applications where power consumption affects runtime. Higher force actuators draw more current, particularly at maximum load. Ensure your power source and wiring can handle the actuator's peak current demand, which typically occurs at maximum load or when stalled.

Step 6: Account for Environmental Factors

Evaluate the operating environment carefully. Indoor climate-controlled applications have modest requirements, but outdoor, marine, or industrial environments demand enhanced protection. Look for IP (Ingress Protection) ratings that indicate sealing against dust and water. IP65 or IP66 ratings provide good protection for most outdoor applications. Marine environments require stainless steel construction or special coatings to resist corrosion.

Temperature extremes affect actuator performance and longevity. Standard actuators typically operate from -20°C to +65°C. Applications outside this range require special consideration. High-temperature industrial processes, cold storage, or outdoor installations in extreme climates may require actuators with extended temperature ratings.

Step 7: Understand Duty Cycle Requirements

Duty cycle refers to the percentage of time an actuator operates versus rests. It's typically expressed as a percentage over a time period, such as "20% at 2 minutes maximum on-time." Most electric actuators aren't designed for continuous operation—the motor and electronics generate heat during operation that must be dissipated during rest periods.

If your application requires frequent cycling or continuous operation, you need industrial actuators specifically rated for high duty cycles or continuous operation. These feature heavier-duty motors, enhanced cooling, and robust construction. Applications like automated manufacturing, continuous adjustment systems, or high-frequency cycling require careful attention to duty cycle specifications.

Actuator Installation Best Practices

Proper installation is crucial for actuator performance, longevity, and safety. While specific requirements vary by actuator type and application, following general best practices ensures reliable operation and helps avoid common installation mistakes that can lead to premature failure or safety issues.

Mounting and Mechanical Considerations

Linear actuators require proper mounting that allows for the angular rotation that typically occurs during operation. Even though the actuator produces linear motion, most applications involve the actuator rotating through an angle as it extends or retracts. For example, when opening a hinged trunk lid or hatch, the actuator must rotate about its mounting points as the lid swings open.

This is why linear actuators feature clevises—the forked end fittings with cross-pin holes—on each end. These clevises accommodate rotation and prevent binding. Always use mounting brackets designed for your specific actuator model, as these ensure proper clevis pin fit and load distribution. Never weld or rigidly fix an actuator that needs to rotate during operation, as this creates enormous side loads that will damage the actuator and mechanism.

For track actuators, ensure the track is mounted to a flat, rigid surface. Any twist or deflection in the mounting surface will bind the carriage and cause premature wear or failure. Track actuators can handle side loads better than rod-style actuators, but they still aren't designed for significant moments or twisting forces perpendicular to the track.

Alignment and Load Distribution

Proper alignment is essential for long actuator life. Misalignment creates side loading—force perpendicular to the actuator's designed load direction—which causes accelerated wear on bearings, seals, and the drive mechanism. When possible, align the actuator so forces are directed along the actuator's centerline.

If your application involves distributed loads or multiple attachment points, ensure forces are balanced. For example, when using two actuators to lift a platform, mount them symmetrically and use synchronized control to prevent one actuator from carrying disproportionate load. Unbalanced loading causes one actuator to work harder, potentially leading to premature failure and creating dangerous instability.

Electrical Connections and Wiring

Make electrical connections according to the actuator's specifications and local electrical codes. Use wire gauges appropriate for the actuator's current draw and the length of the wire run—undersized wiring causes voltage drop that reduces actuator performance and creates fire hazards. For 12VDC and 24VDC systems, voltage drop is particularly significant over long runs.

Protect wiring from abrasion, heat, chemicals, and mechanical damage. In mobile applications, secure wiring so it doesn't flex repeatedly at connection points, which causes wire fatigue and eventual failure. Use proper strain relief at electrical connections. For outdoor or harsh environment installations, use weatherproof connectors and consider running wiring through protective conduit.

When installing multiple actuators with a control box, follow the controller manufacturer's wiring diagrams precisely. Proper wiring polarity is essential—reversed polarity causes the actuator to run backward. Most controllers include protection features, but verifying correct operation before final installation prevents problems.

Testing and Commissioning

Before putting the system into regular service, conduct thorough testing under actual operating conditions. Verify the actuator operates smoothly throughout its full stroke without binding, unusual noise, or vibration. Check that the mechanism reaches desired positions accurately. Test limit switch operation to ensure the actuator stops properly at each end of travel.

For systems with feedback actuators and synchronized control, verify that position feedback operates correctly and multiple actuators maintain synchronization under varying loads. Test any safety features like overload protection, emergency stops, or position limits. Better to identify and correct issues during commissioning than after the system is in use.

Document the installation including mounting dimensions, wiring connections, controller settings, and any application-specific parameters. This documentation proves invaluable for troubleshooting, maintenance, or future modifications.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

Electric actuators generally require minimal maintenance compared to hydraulic or pneumatic systems, but some basic upkeep ensures optimal performance and longevity. Understanding common issues and their solutions enables quick diagnosis when problems occur.

Routine Maintenance

For most electric linear actuators, maintenance consists primarily of keeping the actuator clean and periodically inspecting for wear or damage. Keep the actuator housing and particularly the rod or lead screw free from dirt, debris, and corrosive materials. In dusty or dirty environments, consider adding protective boots or covers to shield the rod when retracted.

Inspect mounting points periodically for loose fasteners—vibration can cause hardware to loosen over time. Check electrical connections for corrosion, damage, or looseness. For outdoor or marine installations, inspect seals and housings for degradation or damage that could allow water ingress. Most electric actuators don't require lubrication—